Linear systems and filtering

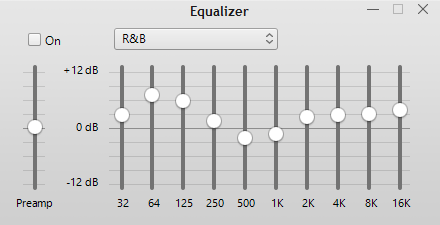

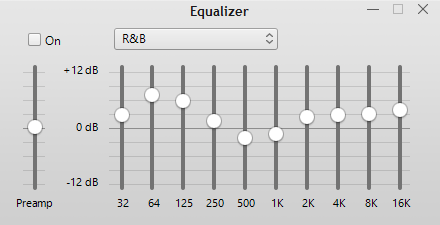

This audio equalizer from Apple iTunes is made possible by a collection of digital frequency-selective filters.

Filtering signals digitally

One of the main advantages of living in the computer/smartphone/wearable age is that digital processing power is widely available!

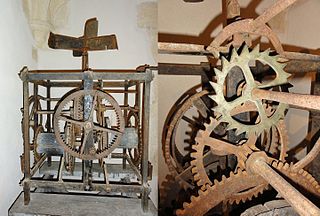

In the olden days, if we wanted to process information, we had to build a machine to accomplish a very specific task. The ability of the processing to adapt to the signal or task was very limited.

A mechanical clock contains a series of gears calibrated to tell time. What if we suddenly decided an hour was composed of 100 minutes instead of 60? We’d need a new clock! (Image credit: Jose Manuel/Wikipedia)

A sextant is specifically constructed to measure angles between objects in the sky and the horizon.

Many of these devices are programmable, allowing us to process signals how we see fit.

So what is filtering?

A filter is a system that permits some information to pass through the system while suppressing other information.

What is a system?

A system performs a mathematical operation, or operations, on one or more input signals, to produce one or more output signals.

A digital filter processes a digital input signal to produce the desired digital output signal.

There are many kinds of digital filters. The equalizer shown earlier is one example. What is an equalizer?

Applications of filtering

The notion of filtering is not new to digital, however. It has shown up for a long time in many mundane places:

- Coffee filter

- Water purification

- Color filter on a camera (or even a stage light)

- Grain separation

- Chemical reactions

Let’s think how we use digital filters in our everyday lives:

- Clean up noise in the video and audio we watch and listen to

- One way to allow multiple cell phones to communicate at the same time

- How a GPS receiver identifies satellites

- How movies play smoothly on high-frame-rate TV’s and computer monitors

What is being filtered in each of these examples?

Peer activity

Instructions: Take few moments and discuss one of the digital filtering applications we identified with someone next to (or seated near) you. Note your answers to these three questions:

- What is the input signal?

- What is the desired output signal?

- What is removed from the input signal? (Or, what is preserved in the output?)

We will discuss your answers as a group.

Let’s talk about systems

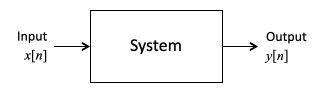

A system (call it T) takes one or more inputs $x_1, x_2, \cdots,$ and produces one or more outputs $y_1, y_2, \cdots,$

Let’s constrain ourselves to one input and one output to start.

We will work with digital systems, but it is more convenient to study discrete-time (DT) systems with continuous-valued inputs $x[n]$ and outputs $y[n]$.

The following diagram describes such a system:

The distinction of working with discrete-valued digital signals is important, but makes analysis much more complicated.

Properties of systems

While a complete discussion of system properties is more appropriate for a later course, there are a couple of important properties that will make our study of filters much easier:

- Linearity

- Time invariance

We already saw linearity in another context: the spectrum of a signal.

Linearity of a system is the same principle: additivity and scaling

For an input $x[n]$, the system $T$ produces the output $y[n] = T(x[n])$

Then, \(y_1[n] = T(x_1[n]), y_2[n] = T(x_2[n]), \rightarrow y_1[n] + y_2[n] = T(x_1[n], + x_2[n]), cy_1[n] = T(cx_1[n]), ay_1[n] + by_2[n] = T(ax_1[n] + bx_2[n].\)

Linearity is a very powerful property that ensures systems are well-behaved:

The system behaves the same no matter how the signal is scaled.

Given a input composed of multiple signals, we can describe the output by processing those component signals individually.

Unfortunately, very little in the world is strictly linear:

Quantization is fundamentally nonlinear, so digital processing is inherently nonlinear.

Real systems have physical limits on the range of possible inputs and outputs. These limits cause saturating, nonlinear behavior.

Fortunately, real systems can be approximately linear over a useful range.

Which is linear/nonlinear?

Consider idealized examples of the following systems. Which are linear?

- Amplifier

- EKG-based heart rate monitor

- Quantizer Now, some mathematical examples:

- $T(x[n]) = (x[n])^2$.

- $T(x[n]) = x[n] - x[n-1]$

- $T(x[n]) = 2$

Time Invariance

Time invariance is another simplifying property that some systems have: processing a time-shifted input produces the output, time-shifted by the same amount. $y[n] = T(x[n]) \rightarrow y[n-n_0] = T(x[n-n_0])$

Some examples:

- $T(x[n]) = x[n+1]$.

- $T(x[n]) = \frac12(x[n] + x[n-1])$

- $T(x[n]) = (x[n])^2$

Let’s show the following are not time-invariant:

- $T(x[n]) = (-1)^n x[n]$

- $T(x[n]) = x[2n]$

Some real-world examples of time-invariant systems:

The audio equalizer

Noise-cancelling headphones

A real-world example that is not time-invariant:

Many systems behave differently as the environment changes, e.g., a car (road, fuel), sound system (humidity, temperature)

Linear, time invariant (LTI) systems

The class of systems that are both linear and time-invariant is a very important class in signal processing theory. While a detailed discussion of these systems will wait for a future course, the frequency representation of these systems is very powerful.

It allows us to describe a filter in terms of what it does to the spectrum of a signal.

Analog systems and filters

Most of the processing of signals is performed in the digital realm

But there are also analog systems and filters

For example, a microphone, before the A-to-D converter, is an analog system

Input: sound waves, analog

Output: voltage signal, analog

The principles are the same (although there are also significant differences)

The concepts are easier to understand and observe with analog systems

So we’ll focus on analog LTI systems for the rest of the lecture

$x\left( t \right) \rightarrow y\left( t \right) \Rightarrow x\left( t - T \right) \rightarrow y(t - T)$

$x_{1}\left( t \right) \rightarrow y_{1}\left( t \right),x_{2}\left( t \right) \rightarrow y_{2}\left( t \right) \Rightarrow ax_{1}\left( t \right) + bx_{2}\left( t \right) \rightarrow ay_{1}\left( t \right) + by_{2}\left( t \right)$

Determine which ones are LTI.

$y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2}x\left( t - \frac{1}{6} \right)$ $y\left( t \right) = x(3t)$ $y\left( t \right) = \frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt}$ $y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi}\frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt} - \frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right)^{2}}\frac{d^{2}x\left( t \right)}{dt^{2}}$ $y\left( t \right) = x\left( t \right)^{2} - x(t/2)$

The response to a single frequency

Let’s see how each of these systems treat a single frequency:

The response to a single frequency $x\left( t \right) = 1e^{i2\pi t},y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2}x\left( t - \frac{1}{6} \right)$

$x\left( t \right) = 1e^{i2\pi t},y\left( t \right) = x(3t)$

$x\left( t \right) = 1e^{i2\pi t},y\left( t \right) = \frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt}$

$x\left( t \right) = 1e^{i2\pi t},y\left( t \right) = \frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt} - \frac{d^{2}x\left( t \right)}{dt^{2}}$

$x\left( t \right) = 1e^{i2\pi t},y\left( t \right) = x\left( t \right)^{2} - x(t/2)$

Frequency response of LTI systems

For LTI systems, the output for a complex exponential is a scaled and shifted version of it (with the same frequency)

$x\left( t \right) = e^{i2\pi ft} \rightarrow y\left( t \right) = A_{f}e^{i2\pi ft + \phi_{f}}$

Since any signal is a combination of complex exponentials, in the frequency domain, each frequency as scaled and shifted by a certain value: $Y\left( f \right) = H(f)X(f)$, $H\left( f \right) = A_{f}e^{i\phi_{f}}$. Describing LTI systems is significantly simpler in the frequency domain rather than the time domain.

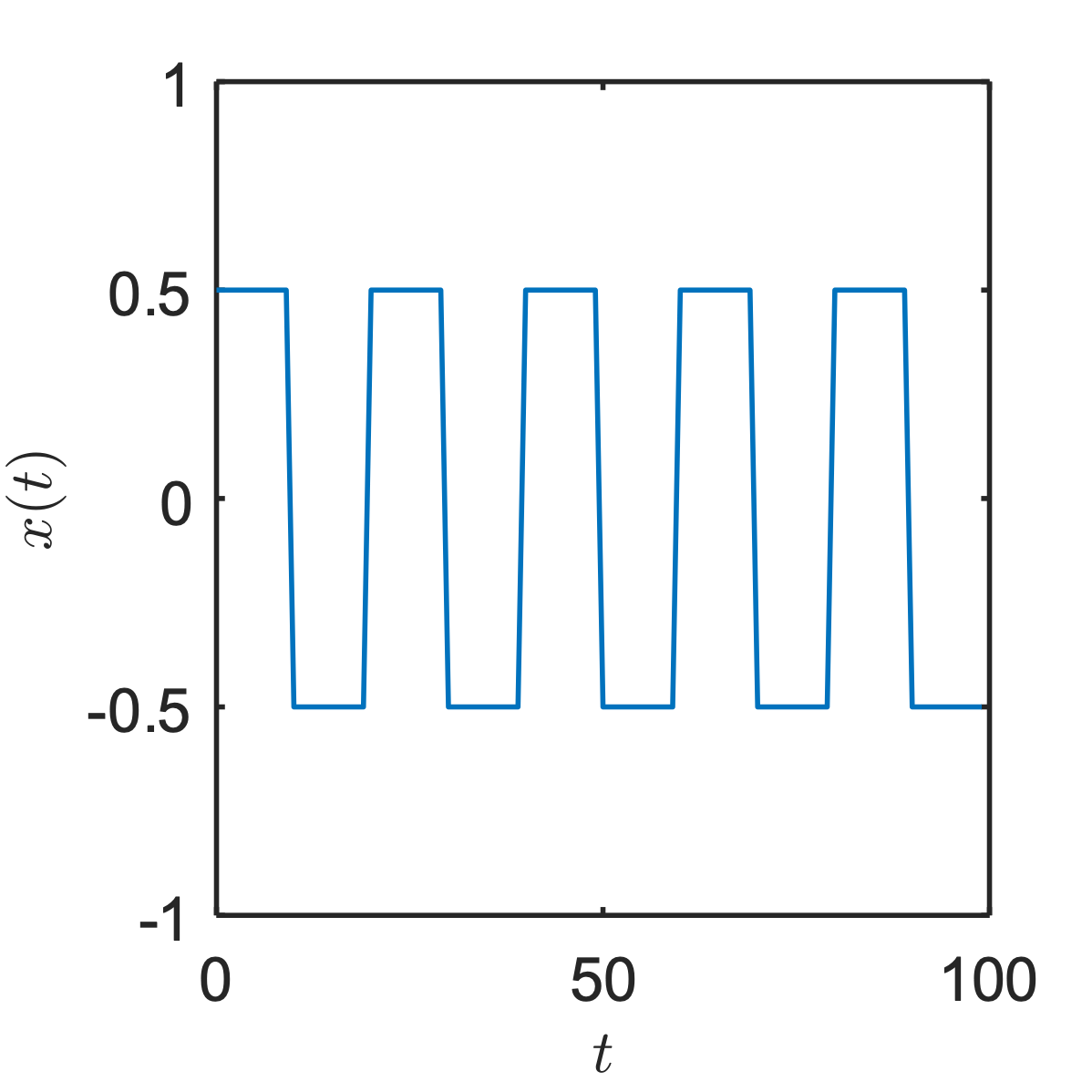

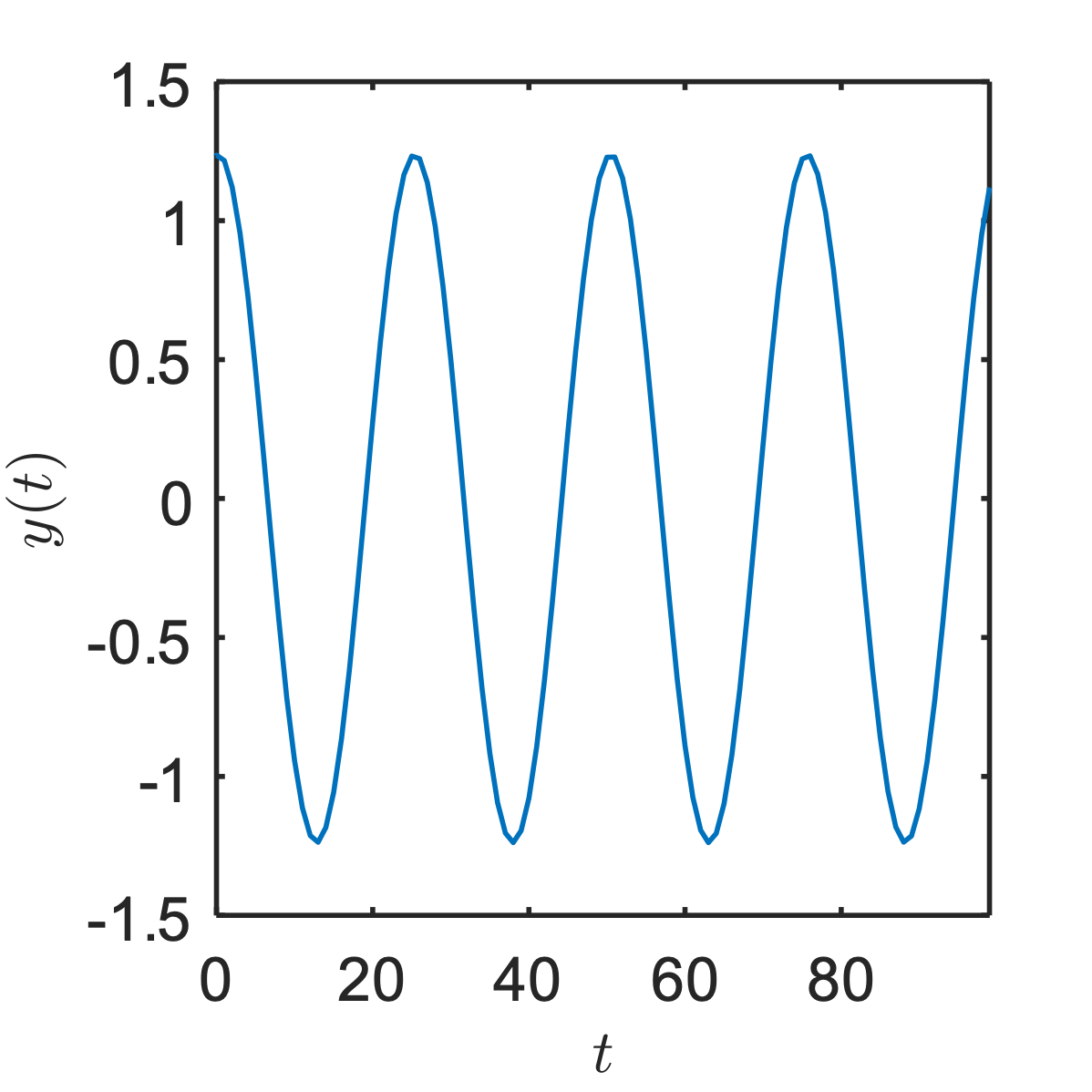

In the time domain:

Sinusoids are scaled and shifted. For non-sinusoids the shape may change.

rightarrow

rightarrow

$y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2}x\left( t - \frac{1}{6} \right) \Rightarrow$

$x\left( t \right) = e^{i2\pi ft} \rightarrow y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2}e^{i2\pi f\left( t - \frac{1}{6} \right)} = \frac{1}{2}e^{- i2\pi f/6}e^{i2\pi ft} \Rightarrow H\left( f \right) = \frac{1}{2}e^{- i2\pi f/6}$

$y\left( t \right) = x(3t)$

$x\left( t \right) = e^{i2\pi ft} \rightarrow y\left( t \right) = e^{i2\pi 3ft}$, for input with frequency $f$ the output has frequency $3f$ => Not LTI

$y\left( t \right) = \frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt}$

$x\left( t \right) = e^{i2\pi ft} \rightarrow y\left( t \right) = (i2\pi f)e^{i2\pi ft} = 2\pi fe^{- i\pi/2}e^{i2\pi ft} \Rightarrow H\left( f \right) = 2\pi fe^{- i\pi/2}$

$y\left( t \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi}\frac{dx\left( t \right)}{dt} - \frac{1}{\left( 2\pi \right)^{2}}\frac{d^{2}x\left( t \right)}{dt^{2}}$

$y\left( t \right) = x\left( t \right)^{2} - x(t/2)$

Recall, real-valued signals have conjugate-symmetric spectra. For the same reason, a real system has a conjugate-symmetric frequency response.

Thus,

$H(f) = H^{\ast}( - f)$

If the input is real, the output of a real filter will also be real, with a symmetric spectrum:

$Y(f) = Y^{\ast}( - f)$

Suppose a signal x(t) has a certain spectrum X(f). If our filter is an LTI system, it effectively scales individual frequencies by fixed values. We call these scaling values the frequency response H(f) of the filter: Image credit: FaberAcoustical

Frequency-selective filters

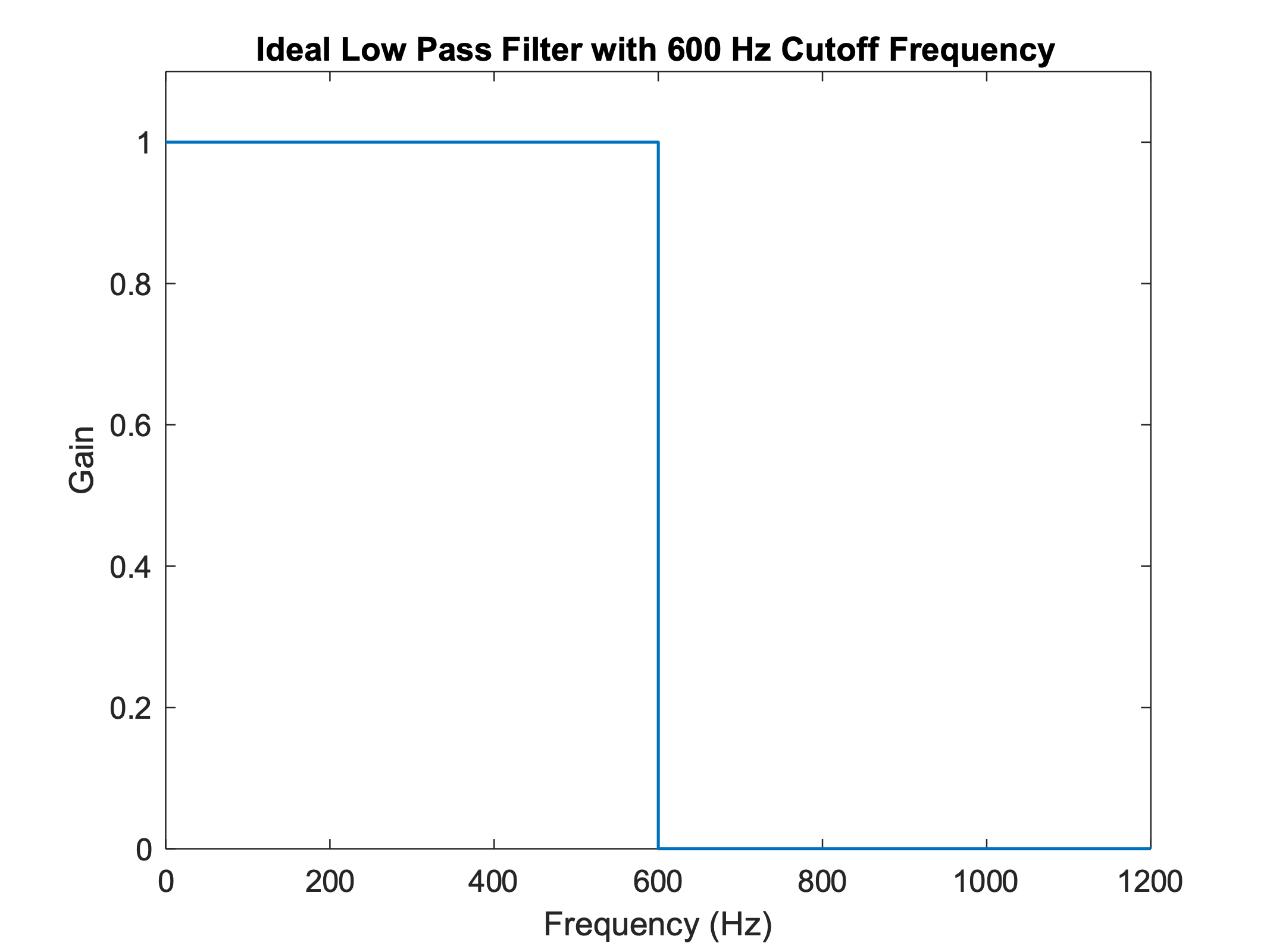

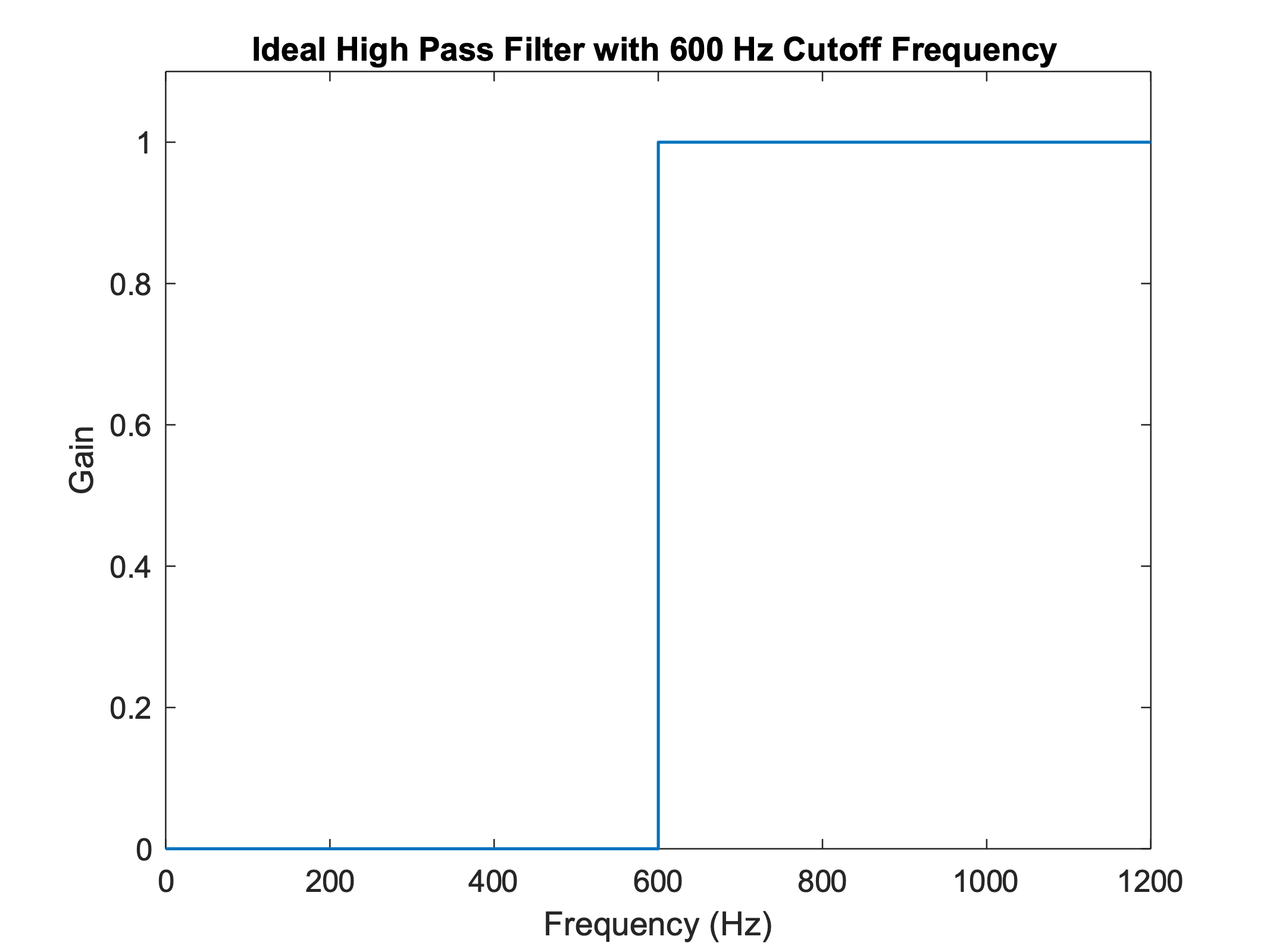

Frequency-selective filters are LTI filters that preserve some frequencies (the passband) and eliminate other frequencies (the stopband) in the signal:

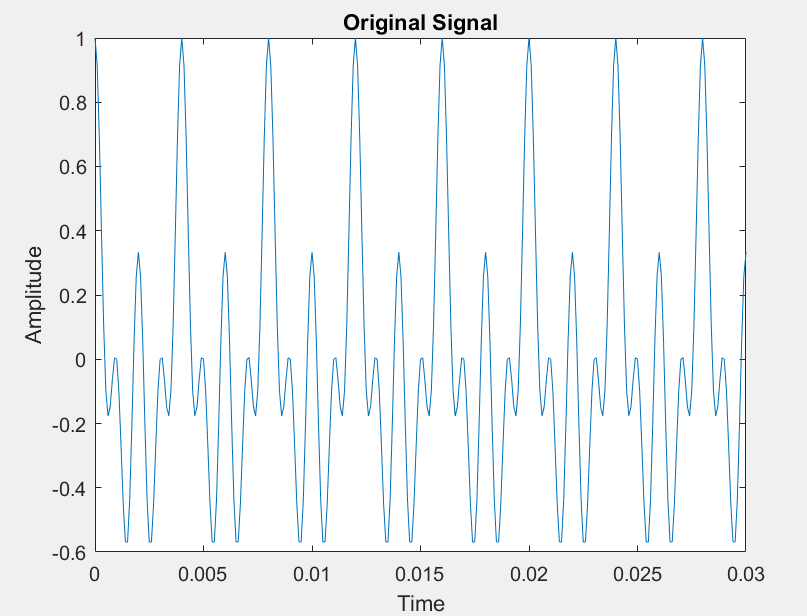

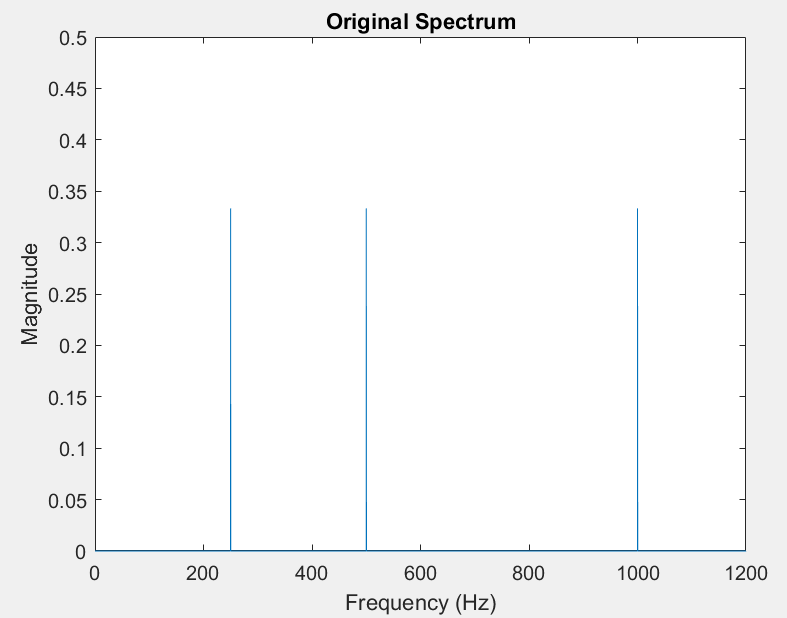

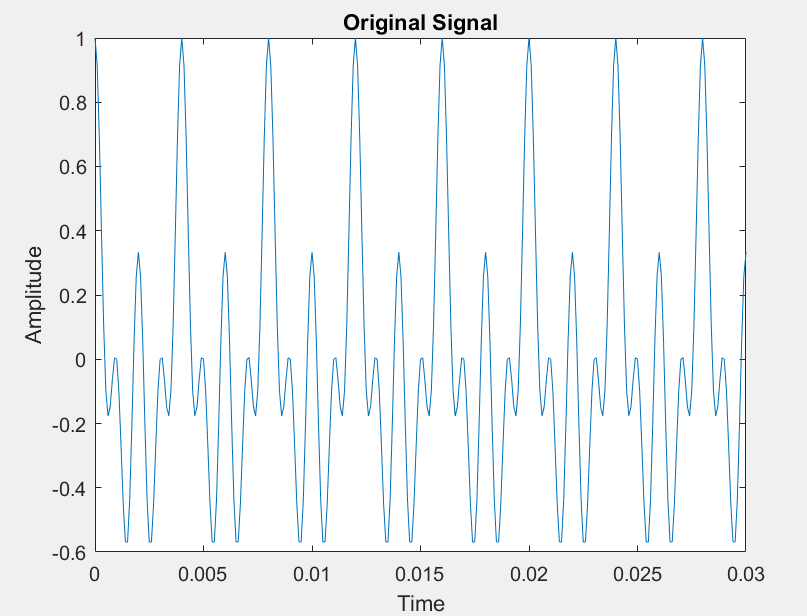

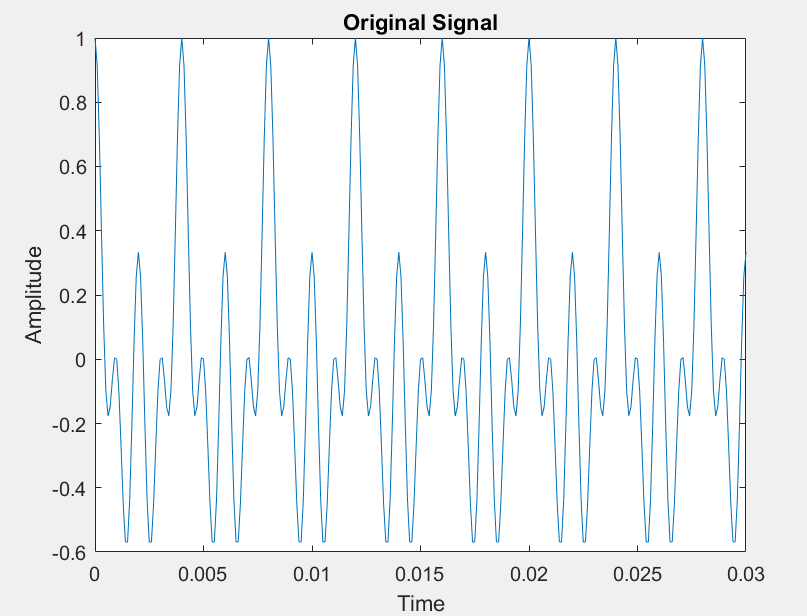

Filtering a sinusoid.

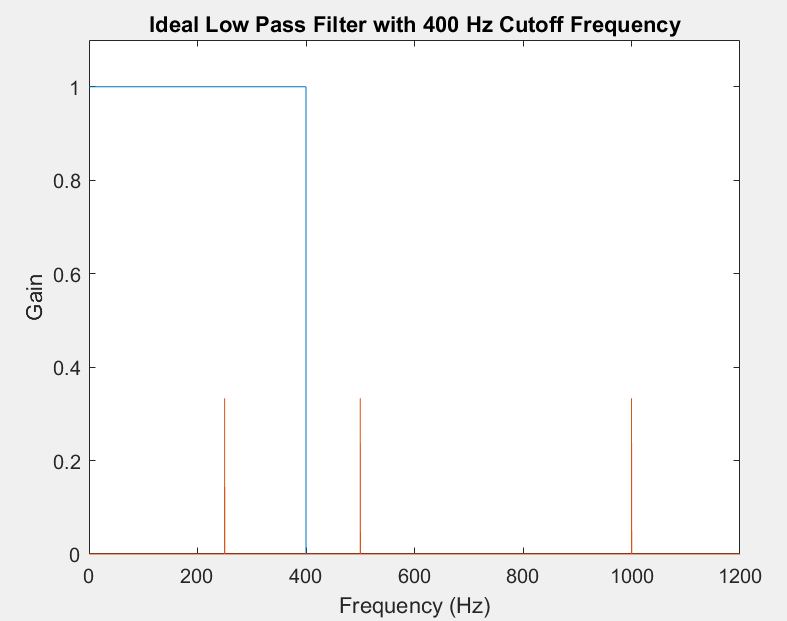

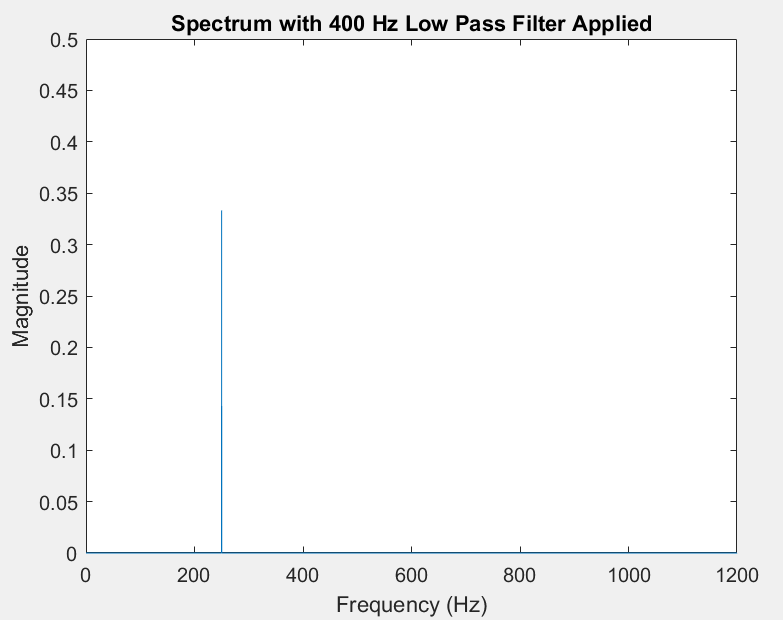

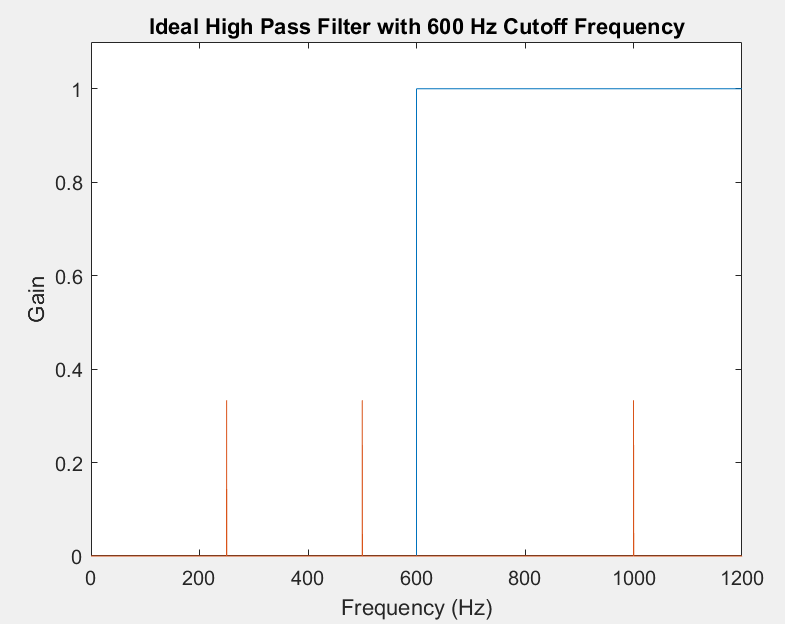

Consider a three-tone signal x(t): $x(t) = \frac13(\cos(2\pi (250)t) + \cos(2\pi (500)t) + \cos(2\pi (1000)t))$

These filters are especially useful when the desired signal occupies a limited set of frequencies.

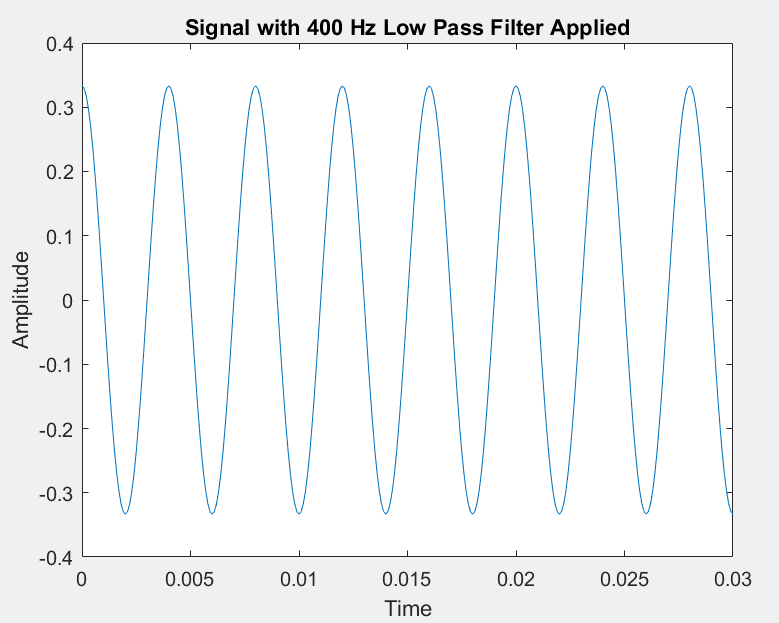

Given a digital low pass filter that corresponds to an analog frequency of 400 Hz, only the lowest-frequency sinusoid will be preserved:

Thus, we observe:

Low pass filter (400 Hz)

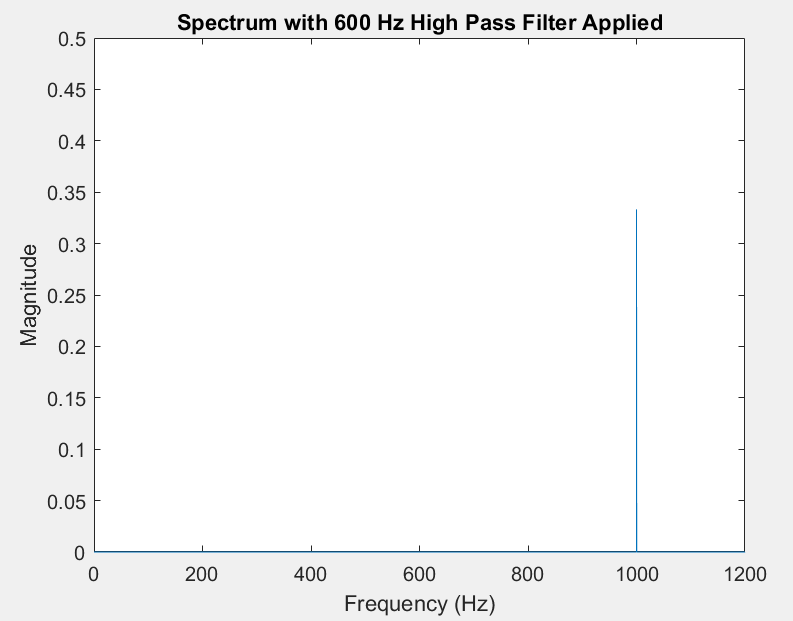

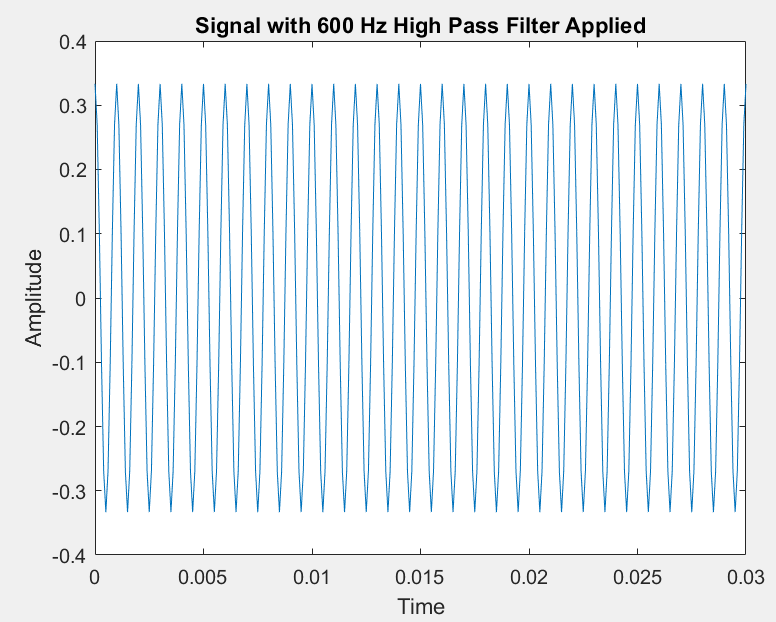

A high pass filter can preserve the highest-frequency sinusoid, while suppressing the others: This filter has a 600 Hz cutoff.

Observe:

High pass filter (600 Hz)

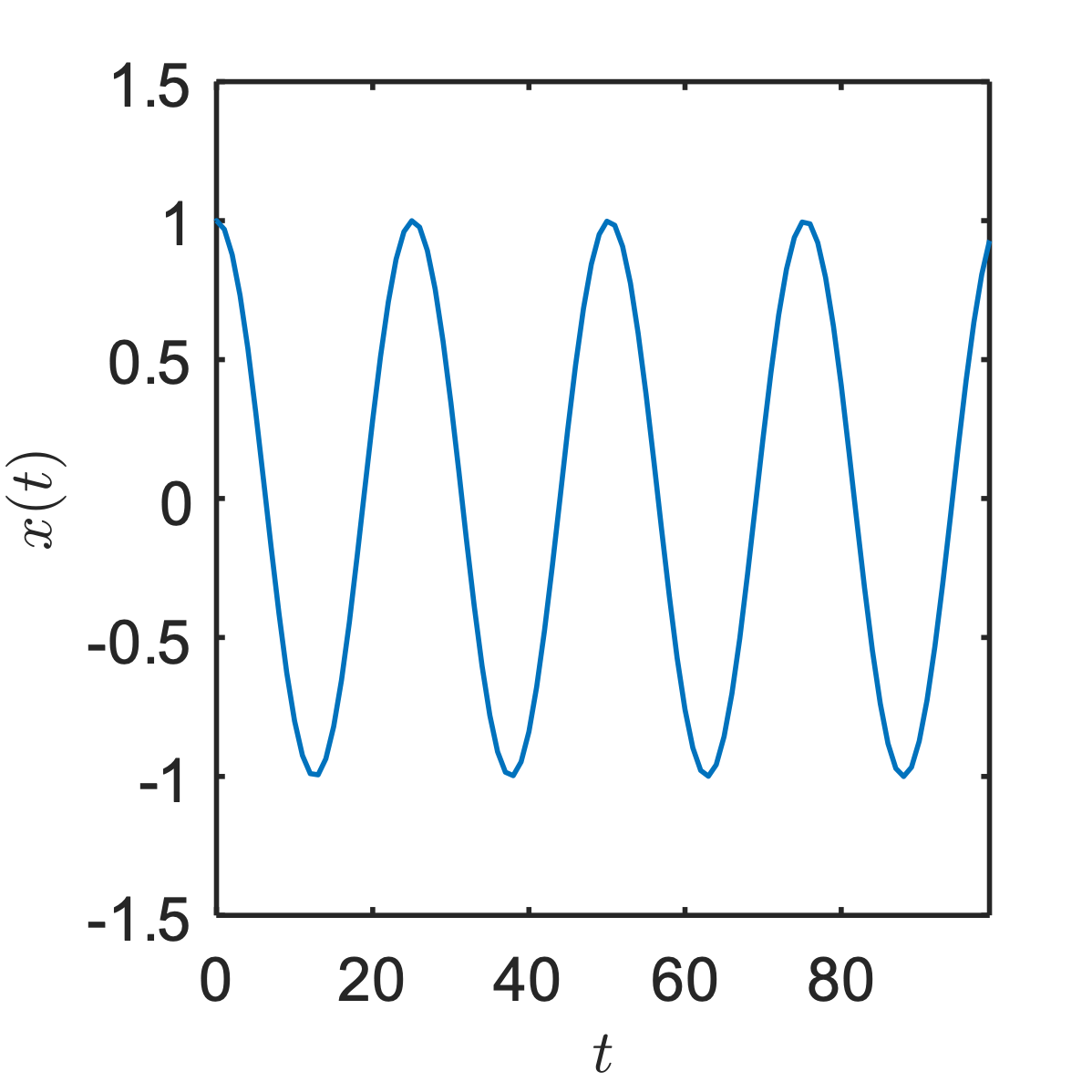

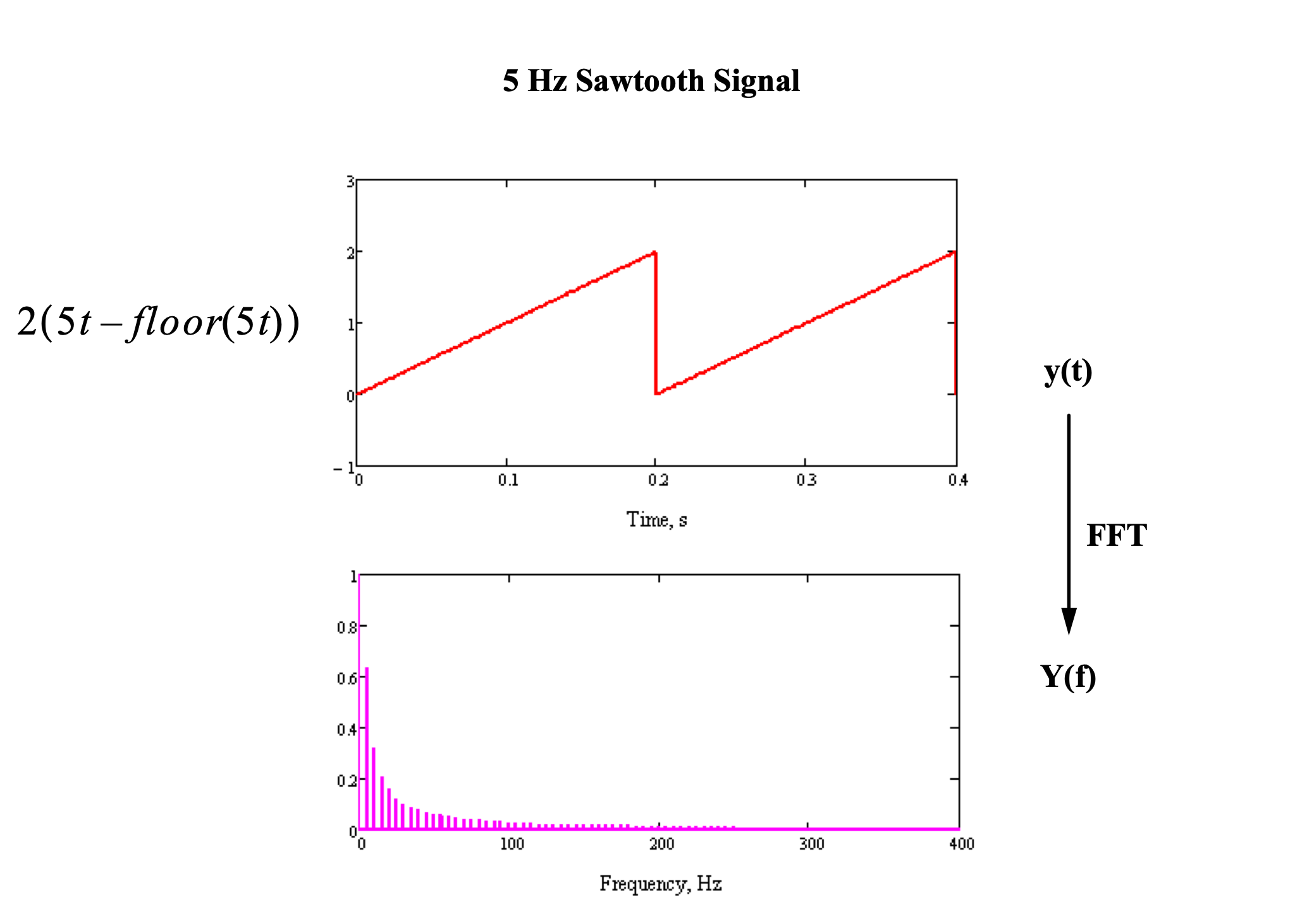

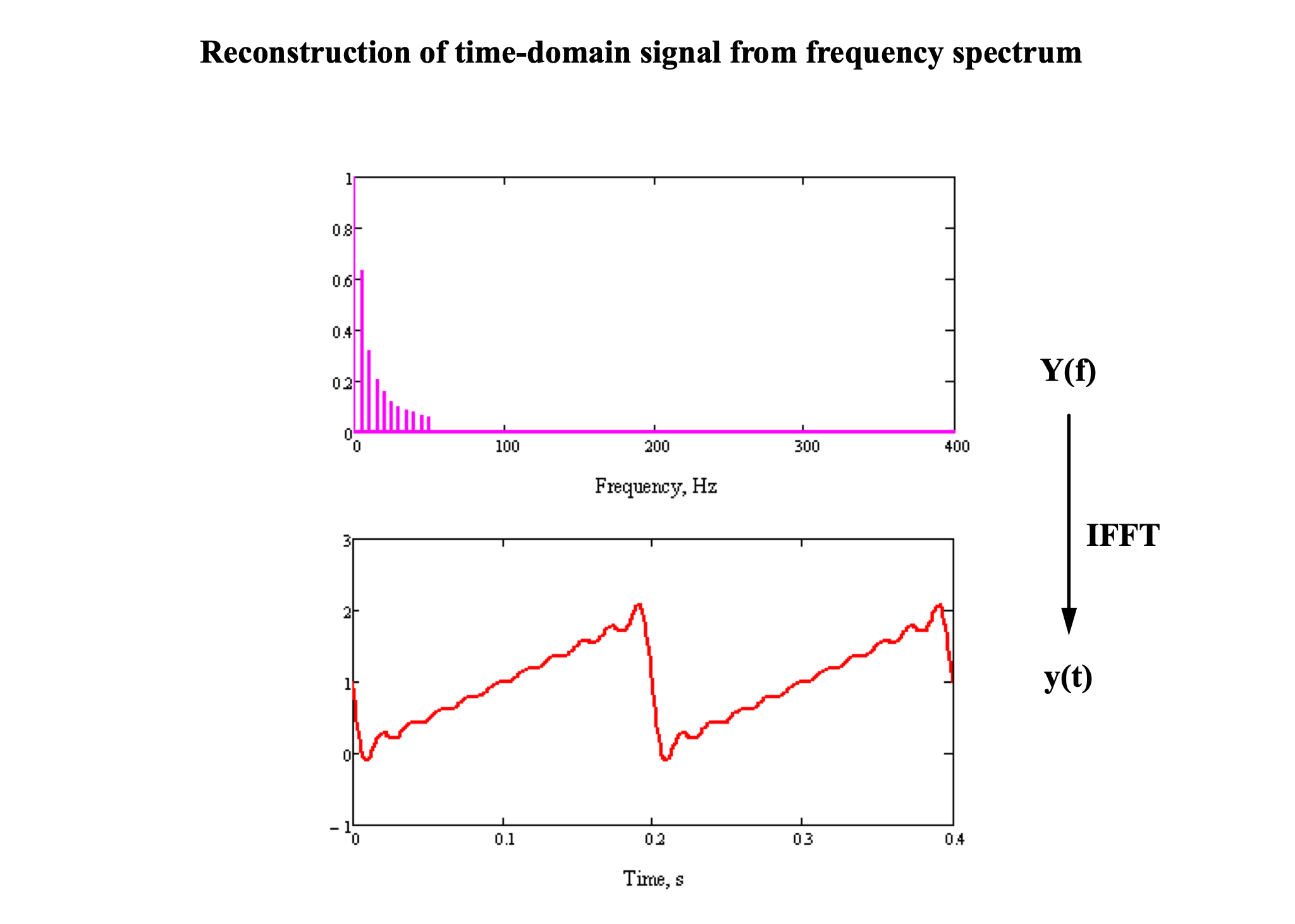

Filtering a sawtooth wave

A sawtooth wave can be constructed from a set of sinusoids of decreasing amplitude: $x(t) = 1 + \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \frac2{k \pi} \cos(2\pi (5k) t + \frac{\pi}2)$.

After filtering above the tenth harmonic (50 Hz):

This graphic equalizer can be considered a set of frequency selective filters:

Each of the frequencies along the horizontal axis represents a range corresponding to the passband of a filter. The decibel (dB) factor selected using the slider represents the passband gain of that filter. The decibel scale is logarithmic, so a factor $> 0$ dB represents amplification (gain $> 1$), while a factor $< 0$ dB represents attenuation (gain $< 1$). The equalizer inputs the sound into each of the filters and adds the outputs together to get the chosen equalizer characteristic. Choose your favorite music and try it out!